110 years ago today, the luxury liner RMS Titanic collided with an iceberg in the North Atlantic Ocean, four days into its maiden voyage from Southampton, England, to New York City. As we have all no doubt seen commemorated on TV and film, the Titanic, the largest ocean liner in service at the time, had more than 2,000 people on board when it struck the iceberg. More than two and a half hours later the ship sank, resulting in the deaths of more than 1,500 passengers and crew. Though our hearts have collectively gone on, the sinking of the Titanic is still considered one of the largest peacetime maritime tragedies in history.

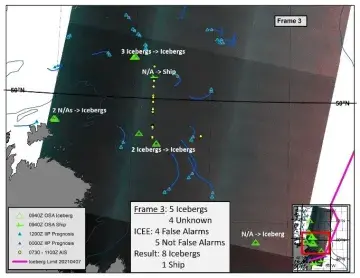

The Science and Technology Directorate (S&T) is developing a new technology to help the U.S. Coast Guard improve maritime safety and navigation in the North Atlantic Ocean to prevent similar collisions in the future. When complete, Project Titanic will fuse satellite-based Synthetic Aperture Radar imagery with ships’ reporting systems to detect, identify, and report iceberg locations to the maritime community.

Believe it or not, floating icebergs like the one that caused the Titanic disaster on April 15, 1912, pose the same navigational hazards today as they did 110 years ago. The event prompted seafaring nations on both sides of the Atlantic to form the International Ice Patrol (IIP). To this day, the Coast Guard conducts this vital mission to protect ships, oil rigs, and other maritime assets from succumbing to a similar fate. When complete, the Project Titanic technology will help the IIP provide even more comprehensive and timely maritime safety information on iceberg locations.

The IIP initially relied on Coast Guard Cutters to survey icebergs but transitioned to aircraft after World War II. Currently, the IIP conducts bi-weekly aircraft missions, for nine days at a time, during the ice season from February through July of each year. During aerial ice reconnaissance missions, the data is collected and aggregated along with data from ships passing through the surveillance area and data collected from oceanographic equipment, like drifting buoys. Ocean currents, wind speed and direction, as well as other environmental data are then factored in to give an overall estimate of iceberg drift and deterioration. Typically, these missions cost the Coast Guard more than $10 million annually and are frequently hampered by bad weather and low visibility.

Using our new S&T-developed technology, which leverages spaced-based imagery, the need for costly aerial ice surveillance will be greatly reduced and our capabilities enhanced. This technology is immune to dark, overcast conditions, or otherwise poor weather that would normally prevent aircraft operations, and the technology can also monitor difficult-to-reach locations to help us predict how heavy an iceberg season to expect. The increasing availability, timeliness, and improved resolution of commercial Synthetic Aperture Radar systems will revolutionize iceberg surveillance.

S&T has also developed Synthetic Aperture Radar-based technologies for other applications like flood response; however, Project Titanic is different from these other S&T efforts because it synthesizes development of global satellite access, faster data collection, and enhanced sensor technology. It also harnesses the versatility of commercial Synthetic Aperture Radar imagery and the efficiency of computers. Because of how far the technology can go with surveying a much wider distance and collecting broader data, we can detect icebergs on an even larger scale than before.

Project Titanic is currently in the developmental phase and the Coast Guard IIP is set to test the technology later this year, before integrating it in 2023. This revolutionary new technology might not be ‘king of the world’, but it will make the North Atlantic safer for ships and prevent peacetime maritime tragedies in the future.